The moment the gate closes, the silent slam reverberates.

The seeds stop moving, stuck in their half-grown state.

The pronghorn are confused, trying to find their way to their new home, spring home, winter home, what season are we in if the gate is closed?

The jaguar can’t roam. Lonely, he climbs a hill. Does he curl into a cave? Does he race back and forth by the fence, like a house-cat watching birds through a window?

The owls can’t fly over, the frogs can’t jump through. They bang against the fence – thump! Thump, thump, like my head.

How do we reach each other?

The moment the gate closes, the distance from me to you is shorter and longer at the same time.

Shorter because it’s now two halves, both of which are smaller than the whole.

Longer because I have to go an extra mile to the port of entry, declare myself, then go the extra mile back to find you.

The moment the gate closes, the earth begins to rumble. The posts dig down 6-8 feet deep. Ground squirrels can dig and go around, but anything larger (a car, say, or a truck) needs a deeper tunnel.

This is for the best, they tell us. The drugs will stop. The violence will stop. The human trafficking will stop. We will catch these things in the net of our iron fence rising to the sky and diving into the desert earth below.

But the drugs, guns, violence, traffickers fling themselves over, landing on the roofs of our neighbors’ houses, squeezing through the checkpoints in tiny bags, parade themselves right through the gate, in trucks covered with bribes and wink-wink-wink.

There’s a lot of money to be made in fences and walls.

Meanwhile, all God’s creatures keep dying in the desert.

The moment the gate closes, the distance from me to you is mirrored back, so I only see me as defender and you as invader. The distance is in opposites – each necessary to define the other.

If there is a wall, you must be invading; I need to defend.

If I need to defend, you must be invading.

The wall—the line—becomes a circle.

The moment the gate closes, animals stop in time, wondering how they will get to their water and food.

The moment the gate closes, humans are startled, and begin solving the new puzzle of how to survive.

If we want to understand the gate, we need to understand fear.

If we want to understand the breaching of the gate, we need to travel beyond the fence, beyond our fear, break out of the circular thinking, and place ourselves on the other side of the mirror.

When you see the gate close, do you breathe a sigh of relief?

When you see the gate close, do you see what we’ve lost?

When you see the gate close, do you wonder how you will visit your ancestors, how you will feed your children?

What does the gate close off from you, from me?

The moment the gate closes, the world changes – in tiny tremors and in lethal floods.

The moment the gate closes, some of us look for ways through, while others of us look to plug the inevitable holes.

The moment the gate closes, papers become important, permission to pass through or not. The moment the gate closes, our hearts begin to rumble. The moment the gate closes, we can look the other way, or we can rise up with renewed commitment. We will survive. We will thrive. We will find a new way through, as heroes always have.

The moment the gate closes, we become adversaries, jailers, guardians, conquerors.

We lose a bit of our story.

The moment the gate closes, migrants become adventurers, saviors, pioneers, pilgrims, trailblazers, champions, defenders, seekers, protagonists of classic novels.

The moment the gate closes, we are cut off.

The moment the gate closes, we are smaller – or larger.

The moment the gate closes, we have a choice.

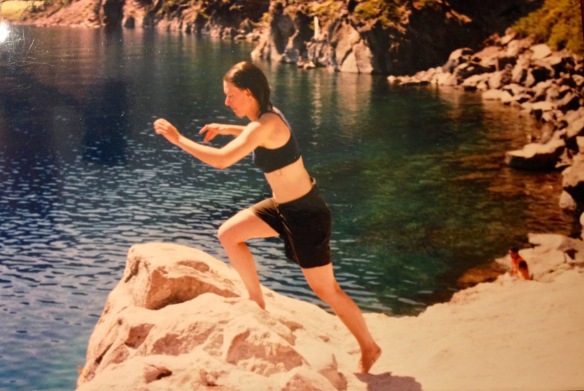

(photo by Saulo Padilla)

(photo by Saulo Padilla)

I spent some time this morning drinking tea and watching this lavender plant. Yep, just watching. I had no phone, no computer, no work, no notebook, no book, just me and a plant. And the sun. And the bees. So many beautiful bees. You can’t tell from that first picture, but the plant is constantly covered in bees, with butterflies fluttering in and out among them.

I spent some time this morning drinking tea and watching this lavender plant. Yep, just watching. I had no phone, no computer, no work, no notebook, no book, just me and a plant. And the sun. And the bees. So many beautiful bees. You can’t tell from that first picture, but the plant is constantly covered in bees, with butterflies fluttering in and out among them.

Poems reveal.

Poems reveal.